Introduction

- Bernadette Oehen, Department of Socio-Economic Sciences, Research Institute for Organic Agriculture (FiBL), Switzerland

- Angelika Hilbeck, ETH Zurich, Switzerland

Agroecology is an idea inspiring more and more people, but it means different things to different people. Altieri (1983) defined it as the application of ecological principles to agriculture. This definition of agroecology includes farmers and farmers’ knowledge, and it sees farmers as stewards of the landscape, of biodiversity and of the diversity of foods. In 2002, Altieri developed his concept further when he proposed that agroecological systems should be based on five ecological principles: 1) recycling biomass and balancing nutrient flows and availability; 2) securing favourable soil conditions for plant growth by enhancing the organic matter; 3) minimizing losses of solar radiation, water and nutrients by managing the microclimate and soil cover, and practising water harvesting; 4) enhancing biological and genetic diversification on cropland; and 5) enhancing beneficial biological interactions and minimizing the use of pesticides.

Some years later, Wezel et al, (2009; 2011) and Gliessmann (2011) stated that agroecology is not only a means of producing food or a scientific discipline, but also a social movement that links producers to consumers, and criticizes the effects of industrialization and the economic framework of the globalized food market. In 2009, the International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development (IAASTD) documented the need for the agroecological transformation of agriculture, food production and consumption and positioned the concept of agroecology in the food policy debate. The report also showed that agroecology is a worldwide process involving conventional, large-scale farmers as well as smallholders, scientists and policymakers, at regional, national and international levels. De Schutter (2010) identifies agroecology as a mode of agricultural development that raises productivity at the field level, reduces rural poverty and contributes to improved nutrition, while helping regions to adapt to climate change. He also points out that the concept of agroecology includes the participation and empowerment of food-insecure groups, because it is impossible to improving their situation without involving them in the process themselves.

De Schutter and Vanloqueren (2011) see agroecology as an effort to mimic ecological processes in agriculture, while increasing productivity and improving efficiency in the use of water, soil, and sunlight as sustainably as possible. Pimbert (2009) goes in the same direction, saying that agroecology is a new form of agricultural production, based on autonomy, prudent use of resources, and cooperation along the agro-food chain. El-Hage Scialabba et al (2014) states that agroecological systems are characterized by the use of a variety of methods, a wide range of crops and, as a new element, different sources of knowledge. And Lampkin et al (2015) sees different agricultural practices and systems as being agroecological in nature. However, according to these authors, they do not count as agroecology unless they integrate multiple practices in order to use synergies at the system level.

To conclude, agroecology is neither a defined system of production nor a production technique. It is a set of principles and practices intended to enhance the sustainability of a farming system, and it is a movement that seeks a new way of food production. Increasingly, agroecology is a science looking at ways of transforming the existing food system, and of further developing agriculture and adapting it to the changing environment – an approach which is vital for food security.

In the literature (Lampkin et al, 2015; Niggli 2015, El-Hage Scialabba et al. 2014) the following production systems are listed as examples of agroecology: integrated pest management (IPM), conservation agriculture (CA), organic farming, mixed crop-livestock/fish systems, agroforestry and permaculture, Low External Input Sustainable Agriculture (LEISA), Low Input Agriculture (LIA).

Among these systems and techniques, only the products of organic farming are subject to worldwide regulation, with laws and private label guidelines. They are traded as such on markets all around the world. The concept of ‘organic farming’ is rooted in the social movements of the early the 20th century, mainly in the German and English-speaking countries. It combines the visions of social reform movements and pioneer farmers who refused to use artificial fertilizers and synthetic pesticides, but were interested instead in concepts of soil fertility, nutrient cycling involving livestock and composts, food quality, and health. Decades later, IFOAM codified this idea into the four principles of organic agriculture: health, ecology, fairness and care. These principals should serve to further develop organic standards worldwide and are deeply rooted in the organic movement. However, they go far beyond the current legislation on organic farming, such as exists in most European countries, the US or Australia. In these countries, many labelled organic products are available to consumers by way of different supply chains: from farm shops and farmers’ markets, to supermarkets and discounters. It cannot be overlooked that large enterprises are also becoming more deeply involved in organic production, not least because of their greater ability to comply with the standards of the retail industry, including organic certification schemes.

Driven by the economic success of organic labels in the food market, there is a risk that certified organic farmers just aim to fulfil the legal requirements. As Lampkin et al (2015) explain, it is debatable whether or not organic farms that achieve certification merely by substituting inputs rather than redesigning their operations, can really be considered agroecological. Even if these farms avoid synthetic fertilizers and pesticides, their dependency on external inputs remains high and the diversity of their crops low.

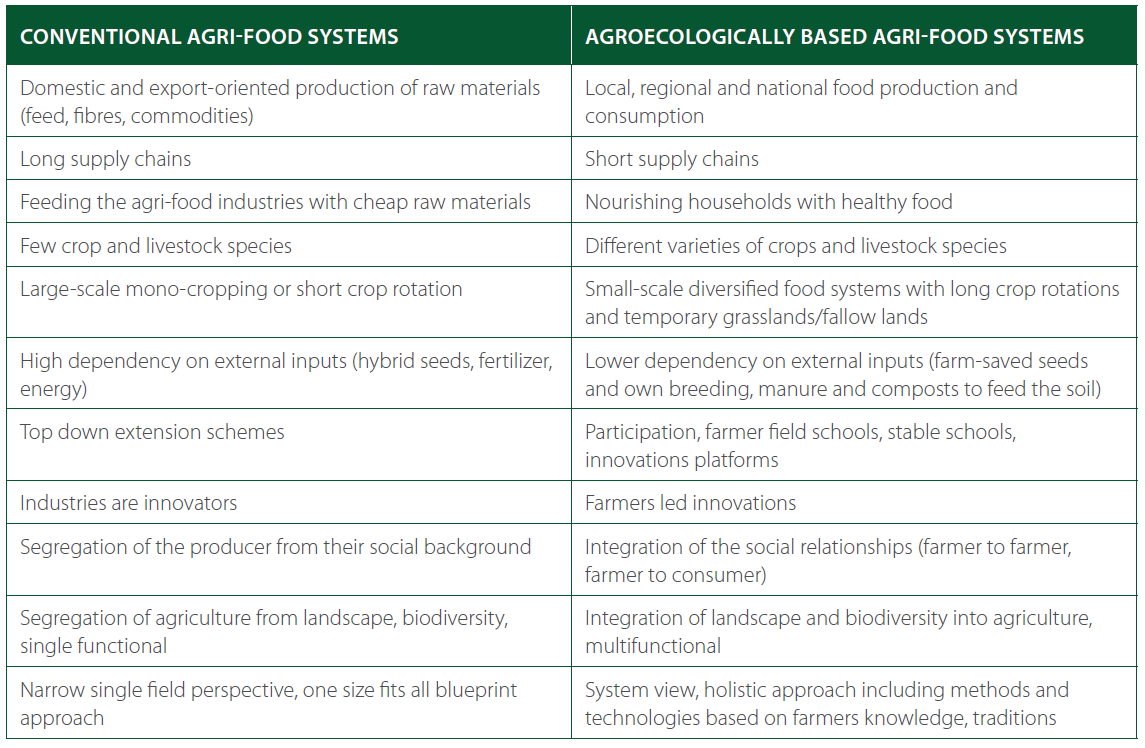

Meanwhile the organic farmers themselves might feel challenged, both by the conventional sector embracing them, and by the agroecologists bringing new concepts into the discussion of sustainable production, such as biodiversity, food diversity, farm-saved seed, food sovereignty, landscapes and participation (see table 1).

Nevertheless, when comparing agroecology and organic farming, the overlapping areas are obvious. In contrast to highly industrialized monoculture, organic farming features the integration of legumes and livestock in order to recycle nutrients; it strives to improve the condition of the soil, especially through increased organic matter content and biological activity; it uses crop rotations; and it further reduces the dependency on external, synthetic inputs. All these measures combine to reduce the environmental externalities caused by the use of toxic agro-chemicals to compensate for these lost ecological functions in industrial monocultures (El-Hage Scialabba, 2014).

What could be learnt from agroecological farm practices and how could it be effectuated in the context of organic agriculture? Just as organic farming contributes to agroecology with its production methods that have been tested in different regions of the world, so does agroecology also add new elements to organic production:

- Use of ecosystem services.

- High diversity of crops and varieties.

- Integration of trees, (fodder) shrubs and hedges.

- Focus on food and communities.

- Food system perspective and access to markets.

- Integration of human knowledge and social capital.

In this brochure, we have brought together a number of experts who are well known in their respective fields. They share their visions of how agriculture can be transformed from its current, destructive form, to one that will help reverse the environmental damage done by industrial agriculture, and one which can feed the global population. While there is broad agreement that such a transformation is imperative for our collective human survival, the proposed trajectories of that transformation differ. How should it be achieved? Can it be achieved within the current economic framework – or will the transformation require an entirely new economic paradigm?

References

Altieri, Miguel A., 1983. Agroecology: the scientific basis of alternative agriculture, Div. of Biol. Control, U.C. Berkeley.

Altieri, Miguel A., 1971 (revised 2002). ‘Agroecology: the science of natural resource management for poor farmers in marginal environments’, in Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 93.1: 1-24.

Wezel, A., and Virginie S., 2009. ‘A quantitative and qualitative historical analysis of the scientific discipline of agroecology’ in International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 7.1: 3-18.

Wezel, A., and Jauneau J-C., 2011. ‘Agroecology – interpretations, approaches and their links to nature conservation, rural development and ecotourism’ in Integrating agriculture, conservation and ecotourism: Examples from the field. Springer Netherlands, 1-25.

Gliessman, S., 2011. ‘Agroecology and food system change’ in Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 35.4: 347-349.

McIntyre, Beverly D., 2009. International assessment of agricultural knowledge, science and technology for development (IAASTD): global report.

Niggli, U., 2015. ‘Incorporating Agroecology Into Organic Research – An Ongoing Challenge’ in Sustainable Agriculture Research 4.3. 149-157.

De Schutter, O., 2010. Agroecology and the right to food, United Nations.

De Schutter, O. and Gaëtan V., 2011. ‘The new green revolution: how twenty-first-century science can feed the world’ in Solutions 2.4: 33-44.

Pimbert, M., 2009. Towards food sovereignty: International Institute for Environment and Development, London, United Kingdom.

El-Hage Scialabba N., Pacini C., Moller S., 2014. Smallholder ecologies. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). 978-92-5-108620-9

Lampkin, N.H., Pearce, B.D., Leake, A.R., Creissen, H., Gerrard, C.L., Girling, R., Lloyd, S., Padel, S., Smith, J., Smith, L.G., Vieweger, A., Wolfe, M.S., 2015. The role of agroecology in sustainable intensification. Report for the Land Use Policy Group. Organic Research Centre, Elm Farm and Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust.